On this page:

- What is Pendred syndrome?

- How does Pendred syndrome affect other parts of the body?

- What causes Pendred syndrome?

- How is Pendred syndrome diagnosed?

- How common is Pendred syndrome?

- Can Pendred syndrome be treated?

- What research is being conducted?

- Where can I find additional information about Pendred syndrome?

What is Pendred syndrome?

Pendred syndrome is a genetic disorder that causes early hearing loss in children. It also can affect the thyroid gland and sometimes creates problems with balance. The syndrome is named after Vaughan Pendred, the physician who first described people with the disorder.

Children who are born with Pendred syndrome may begin to lose their hearing at birth or by the time they are three years old. Usually, their hearing will worsen over time. The loss of hearing often happens suddenly, although some individuals will later regain some hearing. Eventually, some children with Pendred syndrome become totally deaf.

Almost all children with Pendred syndrome have bilateral hearing loss, which means hearing loss in both ears, although one ear may have more hearing loss than the other.

Childhood hearing loss has many causes. Researchers believe that in the United States 50 to 60 percent of cases are due to genetic causes, and 40 to 50 percent of cases result from environmental causes. Health care professionals use different clues, such as when the hearing loss begins and whether there are anatomical differences in the ears, to help determine whether a child has Pendred syndrome or some other type of progressive deafness.

How does Pendred syndrome affect other parts of the body?

Pendred syndrome can make the thyroid gland grow larger. An enlarged thyroid gland is called a goiter. The thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped gland in the front of the neck, just above the collarbones. The thyroid plays a major role in how the body uses energy from food. In children, the thyroid is important for normal growth and development. Children with Pendred syndrome, however, rarely have problems growing and developing properly even if their thyroid is affected. Their levels of thyroid hormones are usually normal.

People with Pendred syndrome are significantly more likely than the general population to develop a goiter in their lifetime, although not everyone who has Pendred syndrome gets a goiter. The typical age for a goiter to develop is in adolescence or early adulthood. If a goiter becomes large, there may be problems with breathing and swallowing. In this case, a health professional should check the goiter and decide whether treatment is necessary. People with Pendred syndrome may need to visit an endocrinologist, who is a specially trained doctor familiar with diseases and disorders that involve the endocrine system, including the thyroid gland.

Pendred syndrome also can affect the vestibular system, which controls balance. Some people with Pendred syndrome will show vestibular weakness when their balance is tested. However, the brain is very good at making up for a weak vestibular system, and most children and adults with Pendred syndrome don't have a problem with their balance or have difficulty doing routine tasks. Some babies with Pendred syndrome may start walking later than other babies, however.

Scientists don't know why some people with Pendred syndrome develop a goiter or have balance problems and others don't.

What causes Pendred syndrome?

Pendred syndrome can be caused by changes, or mutations, in a gene called SLC26A4 (formerly known as the PDS gene) on chromosome 7. Because it is a recessive trait, a child needs to inherit two mutated SLC26A4 genes—one from each parent—to have Pendred syndrome. Since the child's parents are only carriers of a mutation in the SLC26A4 gene, there are no health implications for them.

Couples who are concerned that they could pass Pendred syndrome to their children might want to seek genetic testing. A possible sign that someone might be a carrier of a mutated SLC26A4 gene is a family history of early hearing loss. Another sign is a family member who has both a goiter and hearing loss. However, often there is no family history of Pendred syndrome in the families of children who have the disorder. A mutation in the SLC26A4 gene can be determined by genetic testing of a blood sample.

The decision to have a genetic test is complicated. Most people talk with a genetic counselor trained to help them weigh the medical, emotional, and ethical considerations of testing. A genetic counselor is a health professional who provides information and support to people (and their families) who have a genetic disorder or who are at risk for a genetic disorder.

How is Pendred syndrome diagnosed?

An otolaryngologist (a doctor who specializes in diseases of the ear, nose, throat, head, and neck) or a clinical geneticist will consider hearing loss, inner ear structures, and sometimes the thyroid in diagnosing Pendred syndrome. He or she will evaluate the timing, amount, and pattern of hearing loss and ask questions such as “When did the hearing loss start?”, “Has it worsened over time?”, and “Did it happen suddenly or in stages?” Early hearing loss is one of the most common characteristics of Pendred syndrome; however, this symptom alone doesn’t mean a child has the condition.

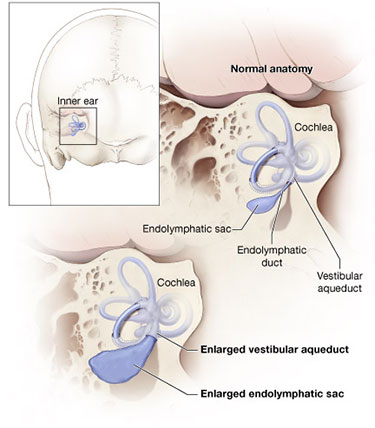

The specialist will use inner ear imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a computed tomography (CT scan) to look for two characteristics of Pendred syndrome. One characteristic might be a cochlea with too few turns. The cochlea is the spiral-shaped part of the inner ear that converts sound into electrical signals that are sent to the brain. A healthy cochlea has two-and-a-half turns, but the cochlea of a person with Pendred syndrome may have only one-and-a-half turns. Not everyone with Pendred syndrome, however, has an abnormal cochlea.

Credit: NIH Medical Arts

A second characteristic of Pendred syndrome is an enlarged vestibular aqueduct (see figure). The vestibular aqueduct is a bony canal that runs from the vestibule (a part of the inner ear between the cochlea and the semicircular canals) to the inside of the skull. Inside the vestibular aqueduct is a fluid-filled tube called the endolymphatic duct, which ends at the balloon-shaped endolymphatic sac. The endolymphatic duct and sac usually are also enlarged.

Experts don’t recommend testing thyroid hormone levels in children with Pendred syndrome, since levels are usually normal. Some children might be given a “perchlorate washout test,” a test that determines whether the thyroid is functioning properly. Although this test is probably the best test for determining thyroid function in Pendred syndrome, it isn’t used often and has largely been replaced by genetic testing. People who have developed a goiter may be referred to an endocrinologist, a doctor who specializes in glandular disorders, to determine whether the goiter is due to Pendred syndrome or to another cause. Goiter is a common feature of Pendred syndrome, but many individuals who develop a goiter don’t have Pendred syndrome. Conversely, many people who have Pendred syndrome never develop a goiter.

How common is Pendred syndrome?

The SLC26A4 gene, which causes Pendred syndrome, accounts for about 5 to 10 percent of hereditary hearing loss. As researchers gain more knowledge about the syndrome and its features, they hope to improve doctors' ability to detect and diagnose the disorder.

Can Pendred syndrome be treated?

Treatment options for Pendred syndrome are available. Because the syndrome is inherited and can involve thyroid and balance problems, many specialists may be involved in treatment, including a primary care physician, an audiologist, an endocrinologist, a clinical geneticist, a genetic counselor, an otolaryngologist, and a speech-language pathologist.

To reduce the likelihood of hearing loss progression, children and adults with Pendred syndrome should avoid contact sports that might lead to head injury; wear head protection when engaged in activities such as bicycle riding and skiing that might lead to head injury; and avoid situations that can lead to barotrauma (extreme, rapid changes in pressure), such as scuba diving or hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Pendred syndrome isn’t curable, but a medical team will work together to encourage informed choices about treatment options. They also can help people prepare for increased hearing loss and other possible long-term consequences of the syndrome.

Children with Pendred syndrome should start early treatment to gain communication skills, such as learning sign language or cued speech or learning to use a hearing aid. Most people with Pendred syndrome will have hearing loss significant enough to be considered eligible for a cochlear implant. A cochlear implant is an electronic device that is surgically inserted into the cochlea. While a cochlear implant doesn’t restore or create normal hearing, it bypasses injured areas of the ear to provide a sense of hearing in the brain. Children as well as adults are eligible to receive an implant.

People with Pendred syndrome who develop a goiter need to have it checked regularly. The type of goiter found in Pendred syndrome is unusual because even though it grows in size, it still continues to make normal amounts of thyroid hormone. Such a goiter often is called a euthyroid goiter.

What research is being conducted?

The NIDCD is funding researchers who are working to understand hearing loss caused by inherited syndromes such as Pendred syndrome as well as from other causes. Researchers also are looking carefully at the characteristics of the disorder and how the syndrome might cause problems in different parts of the body such as the thyroid and inner ear.

Scientists continue to study the genetic basis of Pendred syndrome. The protein that the SLC26A4 gene makes, called pendrin, is found in the inner ear, kidney, and thyroid gland. Researchers have identified more than 150 deafness-causing mutations or alterations of this gene.

By studying mice, scientists are gaining a greater understanding of how an abnormal SLC26A4 gene affects the form and function of different parts of the body. For example, by studying the inner ears of mice with SLC26A4 mutations, scientists now realize that the enlarged vestibular aqueduct associated with Pendred syndrome is not caused by a sudden stop in the normal development of the ear. Studies such as this are important because they help scientists rule out some causes of a disorder while helping to identify areas needing more research. Researchers are hopeful these studies eventually will lead to therapies that can target the basic causes of the condition.

Where can I find additional information about Pendred syndrome?

The NIDCD maintains a directory of organizations that provide information on the normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, taste, smell, voice, speech, and language.

Use the following keywords to help you find organizations that can answer questions and provide information on Pendred syndrome:

For more information, contact us at:

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse

1 Communication Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20892-3456

Toll-free voice: (800) 241-1044

Toll-free TTY: (800) 241-1055

Email: nidcdinfo@nidcd.nih.gov

NIH Pub. No. 13-5875

Updated November 2012

*Note: PDF files require a viewer such as the free Adobe Reader.