On this page:

- What is a vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma)?

- How is a vestibular schwannoma diagnosed?

- How is a vestibular schwannoma treated?

- What is the difference between unilateral and bilateral vestibular schwannomas?

- What is being done about vestibular schwannoma?

- Where can I find more information about vestibular schwannomas?

What is a vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma)?

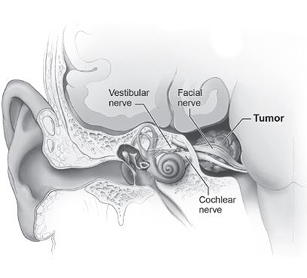

Inner ear with vestibular schwannoma (tumor)

A vestibular schwannoma (also known as acoustic neuroma, acoustic neurinoma, or acoustic neurilemoma) is a benign, usually slow-growing tumor that develops from the balance and hearing nerves supplying the inner ear.

Source: NIH/NIDCD

A vestibular schwannoma (also known as acoustic neuroma, acoustic neurinoma, or acoustic neurilemoma) is a benign, usually slow-growing tumor that develops from the balance and hearing nerves supplying the inner ear. The tumor comes from an overproduction of Schwann cells—the cells that normally wrap around nerve fibers like onion skin to help support and insulate nerves. As the vestibular schwannoma grows, it affects the hearing and balance nerves, usually causing unilateral (one-sided) or asymmetric hearing loss, tinnitus (ringing in the ear), and dizziness/loss of balance. As the tumor grows, it can interfere with the face sensation nerve (the trigeminal nerve), causing facial numbness. Vestibular schwannomas can also affect the facial nerve (for the muscles of the face) causing facial weakness or paralysis on the side of the tumor. If the tumor becomes large, it will eventually press against nearby brain structures (such as the brainstem and the cerebellum), becoming life-threatening.

How is a vestibular schwannoma diagnosed?

Unilateral/asymmetric hearing loss and/or tinnitus and loss of balance/dizziness are early signs of a vestibular schwannoma. Unfortunately, early detection of the tumor is sometimes difficult because the symptoms may be subtle and may not appear in the beginning stages of growth. Also, hearing loss, dizziness, and tinnitus are common symptoms of many middle and inner ear problems (the important point here is that unilateral or asymmetric symptoms are the worrisome ones). Once the symptoms appear, a thorough ear examination and hearing and balance testing (audiogram, electronystagmography, auditory brainstem responses) are essential for proper diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are critical in the early detection of a vestibular schwannoma and are helpful in determining the location and size of a tumor and in planning its microsurgical removal.

How is a vestibular schwannoma treated?

Early diagnosis of a vestibular schwannoma is key to preventing its serious consequences. There are three options for managing a vestibular schwannoma: (1) surgical removal, (2) radiation, and (3) observation. Sometimes, the tumor is surgically removed (excised). The exact type of operation done depends on the size of the tumor and the level of hearing in the affected ear. If the tumor is small, hearing may be saved and accompanying symptoms may improve by removing it to prevent its eventual effect on the hearing nerve. As the tumor grows larger, surgical removal is more complicated because the tumor may have damaged the nerves that control facial movement, hearing, and balance and may also have affected other nerves and structures of the brain.

The removal of tumors affecting the hearing, balance, or facial nerves can sometimes make the patient’s symptoms worse because these nerves may be injured during tumor removal.

As an alternative to conventional surgical techniques, radiosurgery (that is, radiation therapy—the “gamma knife” or LINAC) may be used to reduce the size or limit the growth of the tumor. Radiation therapy is sometimes the preferred option for elderly patients, patients in poor medical health, patients with bilateral vestibular schwannoma (tumor affecting both ears), or patients whose tumor is affecting their only hearing ear. When the tumor is small and not growing, it may be reasonable to “watch” the tumor for growth. MRI scans are used to carefully monitor the tumor for any growth.

What is the difference between unilateral and bilateral vestibular schwannomas?

Unilateral vestibular schwannomas affect only one ear. They account for approximately 8 percent of all tumors inside the skull; approximately one out of every 100,000 individuals per year develops a vestibular schwannoma. Symptoms may develop at any age but usually occur between the ages of 30 and 60 years. Most unilateral vestibular schwannomas are not hereditary and occur sporadically.

Approximately one out of every 100,000 individuals per year develops a vestibular schwannoma.

Bilateral vestibular schwannomas affect both hearing nerves and are usually associated with a genetic disorder called neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Half of affected individuals have inherited the disorder from an affected parent and half seem to have a mutation for the first time in their family. Each child of an affected parent has a 50 percent chance of inheriting the disorder. Unlike those with a unilateral vestibular schwannoma, individuals with NF2 usually develop symptoms in their teens or early adulthood. In addition, patients with NF2 usually develop multiple brain and spinal cord related tumors. They also can develop tumors of the nerves important for swallowing, speech, eye and facial movement, and facial sensation. Determining the best management of the vestibular schwannomas as well as the additional nerve, brain, and spinal cord tumors is more complicated than deciding how to treat a unilateral vestibular schwannoma. Further research is needed to determine the best treatment for individuals with NF2.

Scientists believe that both unilateral and bilateral vestibular schwannomas form following the loss of the function of a gene on chromosome 22. (A gene is a small section of DNA responsible for a particular characteristic like hair color or skin tone). Scientists believe that this particular gene on chromosome 22 produces a protein that controls the growth of Schwann cells. When this gene malfunctions, Schwann cell growth is uncontrolled, resulting in a tumor. Scientists also think that this gene may help control the growth of other types of tumors. In NF2 patients, the faulty gene on chromosome 22 is inherited. For individuals with unilateral vestibular schwannoma, however, some scientists hypothesize that this gene somehow loses its ability to function properly.

What is being done about vestibular schwannoma?

There are three options for managing a vestibular schwannoma: (1) surgical removal, (2) radiation, and (3) observation.

Scientists continue studying the molecular pathways that control normal Schwann cell development to better identify gene mutations that result in vestibular schwannomas. Scientists are working to better understand how the gene works so they can begin to develop new therapies to control the overproduction of Schwann cells in individuals with vestibular schwannoma. Learning more about the way genes help control Schwann cell growth may help prevent other brain tumors. In addition, scientists are developing robotic technology to assist physicians with acoustic neuroma surgery.

Where can I find more information about vestibular schwannomas?

The NIDCD maintains a directory of organizations that provide information on the normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, taste, smell, voice, speech, and language.

For more information, contact us at:

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse

1 Communication Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20892-3456

Toll-free voice: (800) 241-1044

Toll-free TTY: (800) 241-1055

Email: nidcdinfo@nidcd.nih.gov

NIH Pub. No. 99-580

November 2015